As we began to quietly leave the wooden blind from which we’d watched Sandhill Cranes descend onto sandbars in the Platte River at dusk, there was only one thing on my mind. I simply could not get over the fact that I’d spent most of my life living in Nebraska and had never taken the time to see one of nature’s most extraordinary migrations. Perhaps only exceeded by the sights of sounds of whale watching in Alaska, witnessing the influx of tens of thousands of ancient birds and their landings on the shallow waters of the Platte, is truly one of the most breathtaking experiences I have ever had in nature.

I recently heard a TV news report where renowned author, photographer, and conservationist Michael Forsberg said, “It would be like missing Christmas if I didn’t come to the Platte to watch the cranes in the springtime.” I had no idea what I was missing, but I do now.

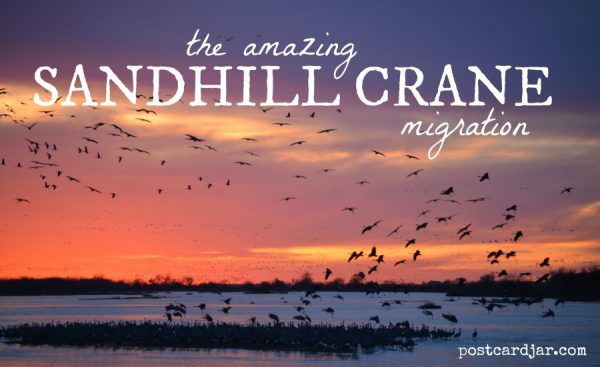

Although beautiful, our pictures do not do the experience justice. The video below (shot on my iPhone) gives you just a glimpse of what we heard and saw.

As a native Nebraskan, I had heard about the annual migration of more than half a million Sandhill Cranes and had even seen hundreds of the birds alongside Interstate 80 when I’d traveled back and forth from my college in Kearney or my first newspaper job in North Platte. But I’d never taken the time to pull off the Interstate and watch these incredible birds or learn about the annual migration that brings them right through the heart of our country and the middle of my state.

Last weekend, I told Steve that I’d read the cranes were beginning to arrive and at the last minute, we decided to make the 2-hour trip on a Saturday afternoon to see for ourselves. We invited my mom (an avid bird watcher) and a college-aged friend of ours to join us and were able to get a late reservation for one of the crane tours at Rowe Sanctuary near Kearney.

Beginning just west of Grand Island, we began to see groups of Sandhill Cranes gathered in the harvested corn fields that afternoon. They were feeding on the left over corn in an effort to store up food and energy for their long migration north. Even from the roadside, cranes could be seen (and heard) socializing and “dancing” to relieve the stress of the migration and strengthen their pair bonds.

We arrived at Iain Nicolson Audubon Center at Rowe Sanctuary where we had a chance to visit with crane experts and watch a short video before a tour guide led us down a dirt path to the wooden blinds where we’d wait for the cranes to return to the river for the night.

Rowe Sanctuary’s viewing blinds are strategically placed along the Platte River to provide excellent views of the Sandhill Cranes, as well as other wildlife. We enjoyed watching the sunset from one of the wooden blinds that is equipped with viewing equipment, benches for sitting, and a great view of the river. We even spotted four otters playing just outside our blind near the river’s edge.

Viewings are scheduled daily during March and early April and last about two hours. We had excellent guides (one who traveled all the way from New Jersey to lead tours) who told us all about the Sandhill Cranes and their migration here. We learned that the cranes can grow to about 4-feet tall (just a foot shorter than my mom) and have been found as far north as Alaska and Eastern Siberia.

In order to reach these destinations, cranes must build up enough energy to complete their long journey and to begin breeding. For the cranes, the Platte River Valley is the most important stopover on this migration. The river provides the perfect spot to rest, and the nearby farmlands and wet meadows offer an abundance of food. Without the energy gained along the Platte, cranes might arrive at their breeding grounds in a weakened condition — where food may be limited until the spring growing season begins.

One of our guides explained how the cranes rely on thermals and tail winds to carry them along. Thermals are rising columns of warm air and when southerly winds start to blow in late March and early April along the Platte. According to Rowe Sancuary’s website, cranes ride thermals so efficiently that they have been seen flying over Mt. Everest (~28,000 feet).

As the sun began to set, we could see dark swarms of cranes in the horizon and slowly, they began to come in view with the naked eye and swirl above the water before descending on the river in the distance. We listened to their loud voices and marveled in their flight overhead. Then, just before the sun was almost set, as the sky turned into incredible shades of purple and orange, one lone crane landed on a sandbar in plain site from our blind. Our group of 20 or so bird watchers was silent. Then another crane landed, and another, and within seconds, hundreds of Sandhill Cranes were settling in right in front of our eyes. As the sun’s light faded into the horizon, the guide asked everyone to stop taking pictures and remain silent.

We all stood by the windows, watching with widened eyes of amazement as thousands of cranes (our guide estimated 10,000 to 20,000) swooped in and landed on the river. I will never forget that moment. All the way home, I couldn’t help but feel the regret of never visiting this place before, the admiration of the long migration of these exquisite birds, and the pride of calling Nebraska home.

No doubt in my mind — we’ll back again next year.

We would like to make a reservation. We live in Omaha. Can we make it a day trip?

The best time to see the cranes is sunrise when the birds leave the river or sunset when they return to the river. If you saw the sunset time, you’d then have your drive back to Omaha after dark. It could be done, but you wouldn’t get home until 10 or 11 at night, is our guess. If you saw the sunrise time, you’d have to leave Omaha in time to check in for the viewing blind by 5:00 or 5:30 in the morning.